What are “unclaimed deposits”?

In ten U.S. states,1 beverage distributors and retailers are required by law to collect small deposits (usually a nickel or dime) on certain packaged beverages.2 When consumers return these beverage containers to a retailer or redemption center, the deposits are returned to consumers. When consumers choose not to redeem their used beverage containers for the deposit value (either because they recycled them through curbside, drop-off, or public space recycling programs--or because they threw them in the trash or littered them), the deposit money is considered “unclaimed.” Other terms are “abandoned” and “unredeemed.” Depending on the state, unclaimed deposit funds are retained by beverage distributors, state agencies, or a combination of the two, and are used for various purposes described below.

Who keeps the unclaimed deposits?

Systems can be generally grouped into two categories: state-managed systems, and systems managed by the beverage industry.

1. State-managed systems

In California and Hawaii, state agencies manage and control the finances of the beverage container deposit system. In California, the agency is CalRecycle; in Hawaii, it is the Department of Health. These agencies collect deposits from distributors when the beverages are sold to retailers. The bottler or distributor pays the deposit directly into a state-managed fund and collects the deposit from the retailer. The retailer then collects the deposit from the consumer. Refunds are paid to the consumers out of the state-managed fund, which is also used to pay for program operation and administration. Hawaii's fund also receives one penny per container from beverage manufacturers to help fund the program. In both states, 100% of unclaimed deposit monies are used by the state agencies*to manage the system, educate the public, and promote markets for recycled material.

2. Beverage industry-managed systems

In the other eight U.S. deposit states, operations and finances are managed by the beverage industry, and unclaimed deposits are either retained by distributors or escheated by the state (in full or in part). Entities include:

2a) Distributors: In Iowa, beverage bottlers and distributors keep all unclaimed deposits.

2b) System operators: Oregon's bottle bill system is operated by the Oregon Beverage Recycling Cooperative (OBRC), which retains all unredeemed deposits to fund bottle collection. The OBRC reports that they also receive $9 million per year in funding from the beverage distributors and grocery retailers. 3

2c) State government: The deposit laws in Connecticut, Massachusetts, New York, Maine, Michigan, and Vermont allow partial or full escheats, whereby distributors and bottlers are required to turn over all or a portion of unclaimed deposits to the state. * The table below shows what proportion of unclaimed deposits escheat to each state, and how the funds are used:

*A note about escheats: Generally speaking, an "escheat" is simply the transfer of unclaimed property to the state or government. When state container deposit laws permit beverage distributors or retailers to keep some or all unclaimed deposits, those are not escheats. "Escheats" in the deposit-recycling world only refer to those unclaimed deposits that state governments keep by law.

How have escheated unclaimed deposits been used?

Escheated unclaimed deposits have been used for both environmental purposes and to supplement a state's general fund.

1. Connecticut

2. Maine: Maine’s escheat law was enacted in 1991. 7 Unlike the laws or provisions in Massachusetts and Michigan, Maine collected only 50% of the abandoned deposits, and the distributors and bottlers retained the other 50%. The revenue was used to fund the Maine Solid Waste Management Agency. Since the state received only half of all unclaimed deposits, and because Maine’s redemption rate for beverage containers was so high, the state chose to repeal the law in 1995, because the State was afraid that they might have to pay out more than it took in. A new escheat law came into effect in 2004, in which all unclaimed deposits escheat to the state except those on containers that are part of a distributor commingling agreement. (See the Maine Quick Facts page for more information on commingling agreements.)

3. Massachusetts: The first escheat law related to container deposit systems was passed in Massachusetts in January 1989. 8 In the first year of implementation, 10% of the unclaimed deposits went into the state’s Clean Environment Fund (CEF) and 90% went into the general fund. Over the next five years, the percent of unclaimed deposits accruing to the CEF increased, while the percentage going into the general fund decreased. By 1995, 100% of escheated unclaimed deposits were earmarked for the CEF.

The intent of Massachusetts’ original law was to use the CEF exclusively for solid waste management, with specific proportions earmarked to provide support for recycling, composting, solid waste source reduction, and other environmental programs related to the bottle bill. 9 However, the actual allocation of the funds has been subject to appropriation by each subsequent legislature. Instead of receiving up to $226 million available from the CEF from FY 1990 to FY 2002, no more than $60 million (27%) was used to stimulate and support recycling, the bottle bill, and other innovative solid waste programs. 10 The other $166 million (73%) went toward Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) overhead costs unrelated to the original mandate of the law. 11

4. Michigan: Michigan’s escheat law was passed in 1989. 12 The law requires 75 percent of the unclaimed deposits to be transferred into the Cleanup and Redevelopment Trust Fund, overseen by the Michigan Department of Treasury, while the remaining 25 percent is to be distributed by the Treasury to retailers as a way to offset their handling costs.

Amended in 1996, the law specifies how the state must distribute its share of the unclaimed deposits. Eighty percent of this Cleanup and Redevelopment Trust Fund is immediately available for appropriation for municipal landfill cost-share grants, matching federal Superfund dollars, response activities addressing public health and environmental problems, redevelopment facilitation, or emergency response actions. Ten percent is deposited into the Community Pollution Prevention Fund, and the remaining 10 percent is deposited into and must remain in the Cleanup and Redevelopment Trust Fund until the amount accrues to a maximum of $200 million.

5. New York: In 2008, New York passed a law to escheat 80% of unclaimed deposits. In 2013, New York passed a law which requires $23 million in unclaimed deposits to go the state Environmental Protection Fund (EPF), with the remaining unredeemed deposits going to the state General Fund. Escheated unclaimed deposits in excess of $122.2 million are also designated to the EPF.13

6. Vermont: Unclaimed deposits in Vermont are used to fund the Clean Water Fund, which is used to help municipalities, farmers and others implement actions that will reduce pollution washing into Vermont’s rivers, streams, lakes, ponds and wetlands.

The Debate on Who Should Keep Unclaimed Deposits

Beer distributors and soft drink bottlers argue that any unredeemed deposits should be utilized to help them offset their costs of managing the container deposit return system. Others argue that the beverage industry is already keeping revenue from the sale of scrap container materials (aluminum, plastic and glass) as well as the “float” (deposits collected from retailers that can be invested for short-term returns), and that unclaimed deposits are tax-free, windfall profits for the bottler/distributor. They argue that unclaimed deposits, like other types of abandoned property, should belong to the state and be used for public benefit. Nearly every deposit state has attempted to escheat the unclaimed deposits as a source of revenue, usually to fund environmental programs.

The economics of each state's program are unique, and depend upon several factors, such as the mix of material types (e.g., aluminum, plastic and glass), the collection mechanism, access to markets for recyclables, and the legislated handling fee. Some distributors are likely making a net profit because the revenue from unredeemed deposits and sale of scrap add up to more than the handling fees paid out and transportation costs.

However, as the mix of materials shifts away from aluminum and toward plastics, programs become more costly.

What are the redemption rates in the deposit states?

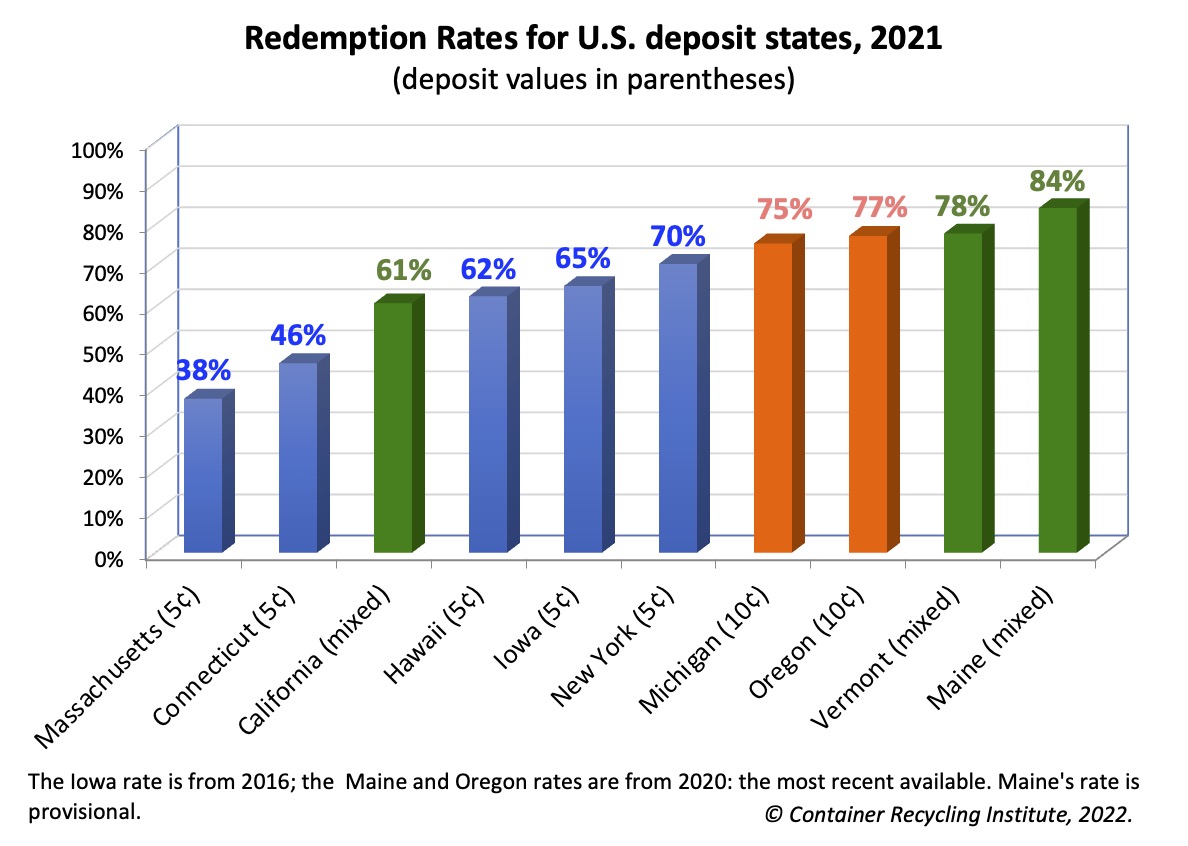

Redemption rates among the 10 deposit states vary widely depending on a variety of factors. The two most important factors are the amount of the deposit ("deposit value"), and consumers' access to redemption options. Higher deposit values and good consumer access to redemption opportunities result in higher return rates and fewer unclaimed deposits.

In states with nickel deposits, the return rates range from 38% in Massachusetts (2021) to 70% in New York (2021). Michigan and Oregon use a 10¢ deposit for all containers and had redemption rates of 75% (Michigan, 2021) and 77% (Oregon, 2020), as the chart below shows.

Three states have mixed deposit values:

- California: the California Redemption Value (CRV) is 5¢ for containers <24 oz., and 10¢ for ≥ 24 oz. (weighted average is 5.4¢).

- Maine: 15¢ deposit for wine & liquor, otherwise 5¢ (weighted average is 5.6¢).

- Vermont: 15¢ deposit for liquor, otherwise 5¢ (weighted average is 5.1¢).

Despite their average deposit values being very similar, Maine and Vermont achieve higher redemption rates than California because they have provided consumers with more redemption opportunities.

Since all the deposit states also have municipal recycling programs, some of the unredeemed containers are recycled either through curbside programs or drop-off sites.

Escheats upheld in court

From 1991 to 1994, the principle of escheating unclaimed deposits survived beverage distributors' legal challenges in three states:

- Maine: In 1991, the beverage industry took the state of Maine to court over the escheat amendment. The law was upheld by a Superior Court, but the Maine Beer and Wine Wholesalers and the Maine Soft Drink Association appealed the ruling. In 1993, the State Supreme Court ruled in favor of the state. 4 The state voluntarily repealed the escheat law in 1995.

- Massachusetts: Suffolk County, MA Superior Court Judge William Bartlett ruled in October 1991 that the Commonwealth's escheat law:

- Did not cause an unconstitutional taking of beverage bottlers’ money;

- Was a proper act of the legislature; and

- That refunds belong to the consumer until escheated to the Commonwealth. The Massachusetts Wholesalers of Malt Beverages appealed this ruling,

However, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court ultimately upheld the law in 1993. 5

- Michigan: In 1991, a lower court ruled that unclaimed deposits were the property of the beverage industry and that the law resulted in an unconstitutional taking by the state. The Department of Treasury appealed the case, and the Michigan United Conservation Clubs (MUCC)--the group that had spearheaded the original escheat campaign--put together an amicus brief for the court. They were joined by several other organizations, including the Container Recycling Institute. In 1994 the Court of Appeals overturned the lower court ruling, claiming that the amendment “constituted a valid exercise of legislative powers.” 6 The State Supreme Court chose not to hear an appeal, effectively affirming the Court of Appeals’ ruling.

Endnotes

1. The states are Oregon, Vermont, New York, Michigan, Connecticut, Iowa, Massachusetts, Maine, California and Hawaii. Guam passed a deposit law in 2011,but it has not yet been implemented.

2. Two states require deposits on carbonated beverages and beer only (Michigan and Massachusetts). Eight states (Maine, Connecticut, California, Iowa, Oregon, New York, Vermont, and Hawaii) require deposits on one or more other types of beverages in addition to beer and soft drinks.

4. Maine Beer & Wine Wholesalers Assín v. State (1993) Me., 619 A.2d 94.

5. Mass Wholesalers of Malt Beverages, Inc. v. Commonwealth (1993) 609 N.E. 2d 67, 414 Mass. 411.

6. Michigan Soft Drink Association v. Department of Treasury (1995) 206 Mich App 392; 522 NW2d 643 lv den 448 Mich 898; 533 NW2d 313.

7. Maine escheat legislation is reprinted at the end of this document.

8. Massachusetts escheat legislation can be found below and at http://www.state.ma.us/legis/laws/mgl/94-323B.htm.

9. See St. 1989, c. 653, s. 70 as codified in G. L. c. 94, s. 323F.

10. E-mail with Tom Collins, Director, Division of Local Mandates, MA State Auditor’s Office, Jan. 22, 2003.

11. Ibid.

12. Michigan escheat legislation can be found below and at www.deq.state.mi.us/documents/deq-wmd-swp-Bottle-Bill.doc.

11. Ibid. Environmental Conservation (ENV) CHAPTER 43-B, ARTICLE 27, TITLE 10, § 27-1012. Deposit and disposition of refund values; registration; reports.

Other sources used: “Deposit Initiator Deposit and Payment Statistics, 2008-2017,” prepared by the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation; March 15, 2017 email from Sean Sylver, Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection, and “Bottle Deposit Information,” prepared by the Michigan Department of Treasury, Office of Revenue and Tax Analysis.

Last Updated on February 1 2023.